The Reformation in Switzerland

Martin Luther did not intend to spark the revolution that

followed the publication of his Ninety-Five Theses. True, he wanted reform, but

not in the way it actually occurred. His treatise found its way to the Pope. A heresy

case was formulated against Luther and he was summoned to Rome. The Elector

Frederick, wishing to guarantee the safety of Luther, persuaded the Pope to

hold the examination (trial) at Augsburg instead, before the Imperial Diet (ie

the General Assembly of the states of the Roman Empire in Germany). Luther appeared

before the Diet in October 1518. The hearings degenerated into a shouting

match, during which Luther stated that he did not consider the papacy part of

the Biblical church. He claimed that Matthew 16v18, where Jesus gives the keys

of the kingdom to Peter, did not give the Pope the exclusive right to interpret

the Bible and that Popes were not infallible.

Not surprisingly, Luther became ‘public enemy number 1’ and

he was excommunicated. He set about redefining church practice in line with

what he had read in the Bible. He also translated the bible from Latin into

German and taught people to read so they could study the Scriptures for

themselves. By 1526, Luther was involved in establishing new churches which

became known as Lutheran churches. Although he changed many things, such as the

practice of indulgences, he continued the practice of infant baptism and

believed that the church should be territorial – ie that any given state should

have an official religion and that all members of that state were expected or

even compelled to be a part. Entry into this state-church was through baptism.

There were some who did not believe that Luther had gone far

enough in his reforms, particularly in the area of communion. The Catholic

church taught that the bread and wine became the actual body and blood of

Christ and that the communion was a re-sacrifice. Luther considered that Christ

was present in the sacrament, though not in the emblems themselves:

“Despite Luther’s independent thinking on the Lord’s Supper, in most

aspects, he remained very close to Roman Catholic theology and practice. Though

he rejected the adoration of the consecrated host, he affirmed the idea of

reverence in the forms of bowing or prostrating oneself before the table. He

insisted that the object of adoration should be Jesus Christ, as He is present

in the sacrament, not the bread and wine.” [http://thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/trevinwax/2008/02/11/luther-vs-zwingli-2-luther-on-the-lords-supper/

]

Meanwhile,

in Switzerland, a number of the followers of Luther were becoming increasingly

unhappy with the trappings of Catholicism which Luther continued to practice. Among

them was

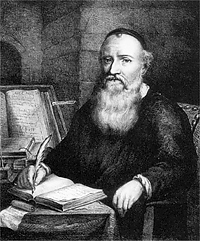

Huldrych Zwingli

Zwingli was born in Switzerland in 1484 and so was only a

year younger than Luther. During his education into the priesthood, he had been

influenced by the writings of Erasmus

and Luther. When he became a minister of the Grossmünster (cathedral)

at Zurich in 1518, he rapidly began preaching on his ideas for reforming the

church. He disapproved of fasting during Lent, promoted marriage for the clergy

(hitherto, they had to be celibate), he attacked the use of images and icons in

worship and he introduced a new form of eucharist to replace the mass. Like Luther,

he believed that the church should be territorial and to that end, he retained

infant baptism.

Switzerland was divided into counties called cantons. Several

of these cantons took up the reformed theology; the rest remained Catholic. Zwingli

formed an alliance between the reformed cantons against the Catholic cantons,

which almost led to war between them. While a full scale war was averted, there

were some battles and Zwingli was killed during one of these skirmishes, in

1531. He was 47 years old.

During this period, church leaders from both sides of the

theological divide would meet together to discuss their differences. These meetings

were called ‘disputations’ and were usually held in public, with many churchmen

and university professors being invited to listen and take part. One such disputation

(the second disputation) took place in September 1523. Around 900 people were

present. The subjects under discussion were icons and images, the sacrificial

nature of the communion, and the necessity of infant baptism. The matter of

icons was not fully resolved. Zwingli, not wishing to cause further falling

out, said he believed that as icons were not used much anyway, it would only be

a matter of time before the churches realised he had no need of them and

dispensed with them.

During the discussion about communion, the question was

raised whether the Zurich city council had the right to make any determination

on the matters of church practice. This was a new development. Up until this

point, the church and state had been inextricably linked, with the formation of

the Holy Roman Empire; church and state acted as one. This was now being

questioned. The subject of the communion itself however, dragged on until 1525,

when, at the Easter celebration, communion was celebrated under Zwingli’s new

liturgy – communion was not an essential requirement for salvation, nor was the

communion a re-enactment of the sacrifice of Christ at Calvary; instead,

communion was celebrated as a commemoration of that sacrifice.

The subject of infant baptism also continued for some years

after the disputation. Eventually, in the interests of peace, Zwingli agreed

with the Zurich council that any changes would be introduced slowly. He published

an article stating the different points of view and held meetings in private

with those who opposed infant baptism. The city council called for a public

debate, following which, the council made the final determination, in favour of

Zwingli and infant baptism. Anyone who refused to have their babies baptised

was forced to leave Zurich and branded a heretic.

Amongst those who disagreed with Zwingli’s position and the

council’s decision was a small group of men who wanted speedier change and more

rapid reform. Especially they wanted infant baptism replaced by baptism for

consenting adults. This group was led by a young man named Conrad Grebel.

To be

continued...